The Origins of Language and the Bouba/Kiki Effect

According to Aleksandra Ćwiek, a doctoral researcher completing a Ph.D. in iconicity in language and sound symbolism at the Leibniz Centre for General Linguistics (ZAS), language barriers are not insurmountable. According to Ćwiek, “There are things that connect us as humans that are deep in our cognition, deep in our nature,” and that “We can show shapes with our voice.” Ćwiek expresses her interest in finding out how sight and sound are connected.

Iconicity studies whether or not there is a connection between how one says something and how it is said. For example, we might talk using a higher-pitched voice when talking about something in the sky and use a lower-pitched voice when talking about something on the ground.

Until recently, many linguists have believed that there is a more-or-less random connection between words and the objects they are attached to. Recent studies in iconicity, however, proves this wrong.

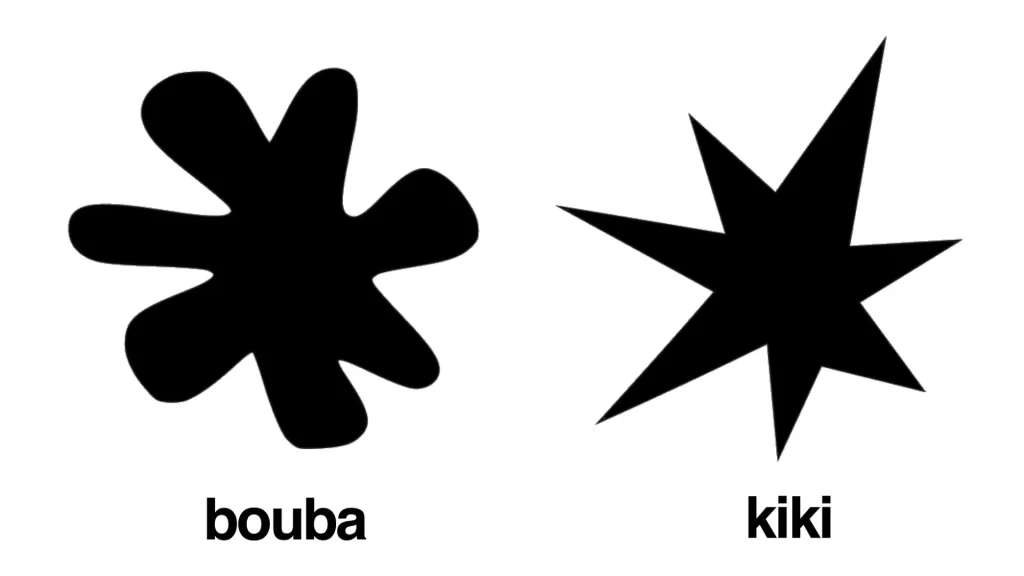

In 1929, Wolfgang Köhler initiated the Bouba/Kiki experiment when he employed the words “maluma” and “takete” to study connections between the human senses. He observed whether his experimental subjects created an association between the word “maluma” with a round shape and the word “takete” with a spiky one. Since then, the words used in the experiment have been switched to “bouba” and “kiki,” with “bouba” being linked to a round shape and “kiki” being linked to a spiky one.

Using the Bouba/Kiki experiment, Ćwiek and her colleagues have created a new experiment that uses subjects from around the world, with the goal of finding the cross-cultural nature of the Bouba/Kiki effect. 900 subjects across 25 different languages are tested, and Ćwiek expresses that, “We took it to another level by using the same methodology across different languages.” She adds, “This is the first time that we have investigated that many languages with the same experiment.”

In Ćwiek’s experiment, the subjects from across different cultures and languages are given a round image and a spiky image. Then, the researchers play the two words for them to hear. Following this procedure, subjects are told to assign each word to one of the two shapes.

According to the results of Ćwiek’s experiment, over 70% of the subjects confirm the Bouba/Kiki effect, and speakers of 17 (out of the 25) languages also confirm the effect.

However, the effect isn’t universal, and Ćwiek explains that this is due to linguistic mechanisms that override the effect and that some languages just forbid certain structures. For example, in Romanian, “bouba” sounds like a word for wound, hence lessening the link to a round shape. Additionally, “bouba” and “kiki” are not native syllables in Chinese, so the experiment may just not have worked as well for Chinese.

Ćwiek doesn’t think there is one original language, but she does think that the sensory crossover found from her experiment can show how language is developed, stating, “These correspondences, I feel they are engraved in us in a way they might have helped us to build words at the very beginning.” She adds, “When we don’t share a language it’s easier to rely on resemblance than to rely on something very abstract. If the signal gets to you then you’re more likely to repeat it and it’s more likely to be coined as a term.”

Today, similar studies of iconicity is frequently employed in marketing. For example, brands create names for their products by taking advantage of the warmth of “bouba” in the mouth and the break of the airstream of the lungs from “kiki,” successfully making names that suit the products well. All in all, Ćwiek’s experiment shows that there is a certain degree of similarity of experience among humans. She believes that humans should use their ability to draw with their voices to cross cultural boundaries.

“It has a lot of power across languages. We focus too much on geographical borders; we are all humans.”